- Home /

- News /

- General news

Exhibition shows suffering, resilience and hope

3 May 2024

Uncle Murray Harrison, a Wotjobaluk man from Bruthen in Gippsland, was just ten years old when he was taken from his home and placed in a youth detention centre in Melbourne in 1948.

Though he was part of a caring family, authorities believed his relatively fair skin made him an ideal candidate to be assimilated into the white majority.

Uncle Murray’s story is one of many that feature in a photography exhibit held at Parliament House this week.

“ It wasn't some colonial government, or some colonising government of England, it was us right here. ”

Photographer David G. Jones

Photographer David G. Jones says, while the story of the Stolen Generations is widely known, Australia still needs to do more to acknowledge the ongoing hurt and intergenerational trauma caused by decisions made by our own governments.

‘It wasn't some colonial government, or some colonising government of England, it was us right here. People were taken right up until the ‘60s, and that's the Australian government,’ he says.

The exhibition, and an accompanying book of photographs, aims to create empathy for those affected by the policy of child removal.

‘When Uncle Murray Harrison agreed to be photographed, he said “this might work, where words have failed”. When he said that it pushed me to take the project from a couple of photographs to an exhibition and then on to a book,’ David Jones says.

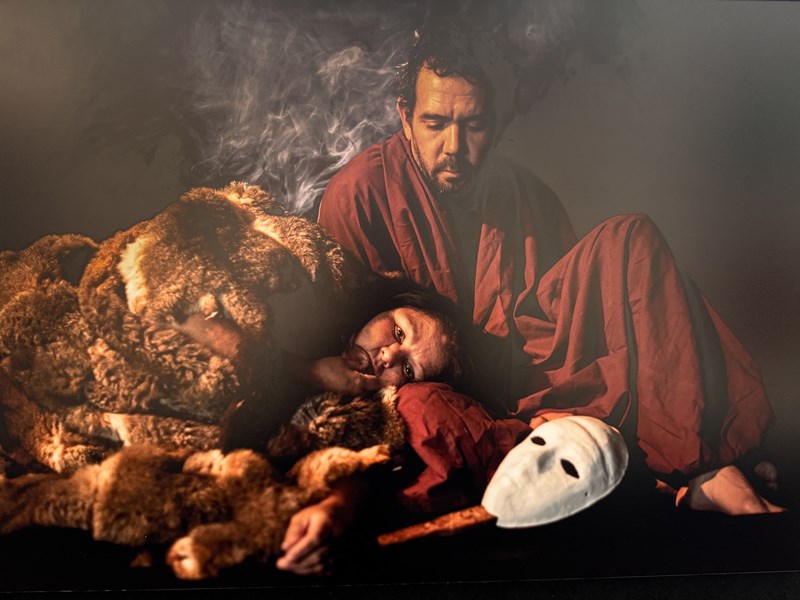

'I tried to portray them in such a way that still preserve their dignity and showed their resilience, yet showed also showed hope despite the underlying suffering that they've actually been through.’

A recurring motif in the photographs is the white mask.

‘They were taken, but they were forced to live behind this white mask. They were taught to be ashamed of their Aboriginality,’ the photographer says.

‘So basically it became built into them that they were ashamed to even acknowledge the fact that they were Aboriginal. Some people I have spoken to are still apprehensive about it because of that sense of shame that we sort of pushed onto them,’ he says.

'The photographs are dark, very dark. Hence that type of lighting. I just wanted to feature the pain that they experienced, but also the hope and at the same time to preserve the dignity within those people,' he says.