- Home /

- News /

- General news

Wartime response remembered

15 August 2025 Read research papers

It was a Wednesday in September 1941 during the height of World War II and Victorian MPs were gathered in the Legislative Assembly chamber at Parliament House.

‘We are facing the greatest crisis in the history of Australia, and we must not place too much reliance on the services of school boys of sixteen years. It is to our women folk that we have to look for assistance.’ said Ivy Weber, Member for Nunawading.

The wartime Victorian Parliament included just two women, Ivy Weber and Fanny Brownbill who spent a lot of their time courageously advocating for the active participation of women in the state’s war response.

Eight decades on, it is clear just how instrumental Victorian women were during that period of time.

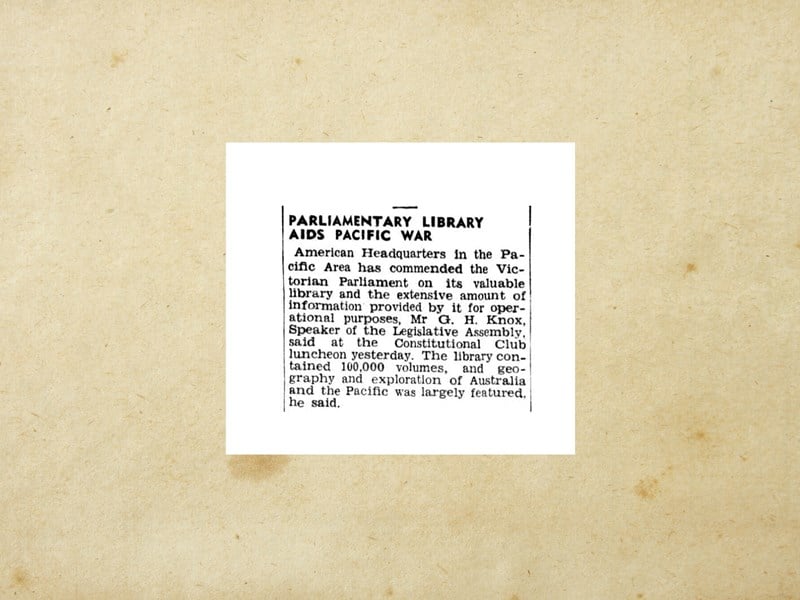

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of Victory in the Pacific Day (‘VP Day’) that marked the end of World War II, the Victorian Parliamentary Library has released two research papers, one examining the wartime experiences of Victorian women and women Members and another exploring how the Victorian Parliament and its Members continued to govern in the face of war abroad and life on the home front.

“ In total around 51,000 Australian women served in one of the services. ”

The war period was a time of change for many women. While women wanted to play a more active role in the war effort, the federal government and military leaders were hesitant. Paul Hasluck, in the official history of Australia’s war, blames ‘male obtuseness’ for the delay in making ‘better use of women in the war effort’.

In early 1939, a delegation of women met with Defence Minister Geoffrey Street and told him that ‘in the last war we stood behind our men, but in this emergency, we would like to stand with them’.

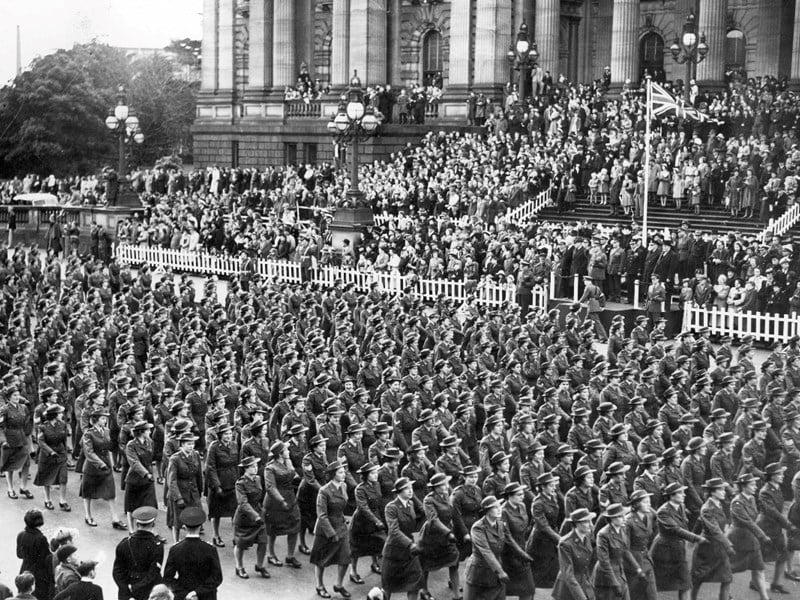

Not long after, Victorian women could serve alongside their husbands, brothers, fathers and sons who were in the army, air force and navy when the corresponding women’s services were formed: the Australian Women’s Army Service (AWAS), the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Airforce (WAAAF) and the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service. Like in World War I, the Australian Army Nursing Service and Voluntary Aids provided medical care to wounded and ill soldiers throughout the conflict.

While for many women joining the service was a chance to learn new skills and experience some independence it was not totally smooth sailing.

‘At first, it was a total battle to get men to accept us as workers,’ an AWAS member recalls. ‘They were very hostile … Articles in the press didn’t help. “Servicewomen keep their femininity,” and “Girls don’t lose their femininity in barracks.” … The soldiers saw us as playing at work.’

In total around 51,000 Australian women served in one of the services. Some worked as cooks and waiters, others as drivers, electricians and mechanics (for both cars and planes). Many worked as Morse Code operators, telegraphists, visual signallers and some were trained in breaking the Japanese Kana code.

By the end of the war, it was clear just how much these enlisted women had contributed to the war effort. Commander J.B. Newman of the Royal Australian Navy, commented, ‘I don’t know how we would get along without them’.

Fundraising efforts for the war in Victoria were primarily run by female volunteers and the Red Cross was by far the largest women’s organisation during the war years. The Victorian Red Cross raised a total of £4,492,041, which is equal to AUD$388,432,710 today. By comparison, the Royal Children’s Hospital’s Good Friday Appeal raises around $20 million each year.

Even working women made time to volunteer to the war response. Outside of the chamber and on top of her parliamentary responsibilities, Fanny Brownbill helped with the creation of the Geelong Red Cross Emergency Service and was Vice President of the Geelong Branch by 1943.

Every Monday afternoon, she would work the sewing machines at the branch and would take advantage of her commute to and from Melbourne to knit garments for the Australian Comforts Fund. As the only two women Members in Parliament at the time, Brownbill and Weber had agreed not to knit during debates in the chamber.

While not directly responsible for defence, the Victorian Parliament played a significant role during the 1939–45 conflict. The State Emergency Council for Civil Defence was officially appointed by the Victorian Government in October 1939 under the National Security (Emergency Powers) Act 1939. The Council developed plans for evacuating cities, restricting lighting, protecting public utilities and air raid warnings.

Parliament also appointed a State War Advisory Committee, consisting of representatives of all parties, the ministry and the Legislative Council. These bodies engaged in extensive planning and activity centred on civil defence and economic support for the war effort, including planning and exercises for air raids. At the height of the war, over 60,000 Victorians were involved in air raid precautions work around the state.

Weber was one of the first parliamentarians to complete an air raid preparation course in 1941 and was disappointed that more Members hadn’t joined her. ‘If an air raid occurred in Melbourne tonight’, she said in the chamber, ‘what would honourable members generally do?.’

The second daylight air raid test in April 1942 was a success, despite some issues with overcrowding. Along with everyone in the city, over 1,000 public servants, marshalled by wardens, evacuated their offices and filed into the nearest trenches, which were in the Treasury Gardens.

At Parliament House, the evacuation sub-committee, led by Weber, ushered Members in the building and parliamentary staff into trenches dug in the Parliamentary Gardens. These trenches were later described as being ‘constructed most elaborately; even a miner would have approved of the way they were timbered’.

A black-out trial in Melbourne in September 1941 was seen as reasonably successful—vehicle headlights were dimmed, and all advertising and display signs were dark, however things did not always go exactly to plan for the Victorian Parliament. A news report noted how Parliament House had effectively ‘let the side down’ with light being visible from windows on the northern side of the building.

In the same month, as part of an air raid precautions demonstration, a first aid party of parliamentary staff had been photographed lowering a bandaged dummy from the roof to a prepared casualty room.

Eighty years on, and published in tribute to the wartime efforts of Victorians, the Parliamentary Library's two research papers provide a snapshot of some of the ways in which Victoria responded to the call of service required to protect and defend the state and the nation.

Photographs: The Argus, courtesy State Library Victoria